In Conversation: poet Julia Bouwsma - Part 1

Poet,

Julia Bouwsma

In Conversation - PART ONE

Image credit: Mary Pols, Maine Women Magazine.

www.juliabouwsma.com

#JuliaBouwsma

Sometimes you discover a writer whose prose transcend the moment. When I discovered the work of poet, Julia Bouwsma, I immediately felt a connection to her work. This was a visceral reaction, one that I acted upon! I knew that I needed to learn more about this poet, how she lives “off-grid” and her methodology for working creatively.

Julia and I have begun a collaboration that will culminate in an art installation - to be installed initially in 2020. All collaborations have a beginning and this one starts here, with a two part conversation about life, choices and making strong work. This is Part One where Julia discusses her choice to live rurally independent and the impact on her poetry and writing. In Part Two, we will delve more deeply into Julia’s published work and the genre of documentary poetry. Julia offers many thoughtful insights on how to live and create art.

About Julia:

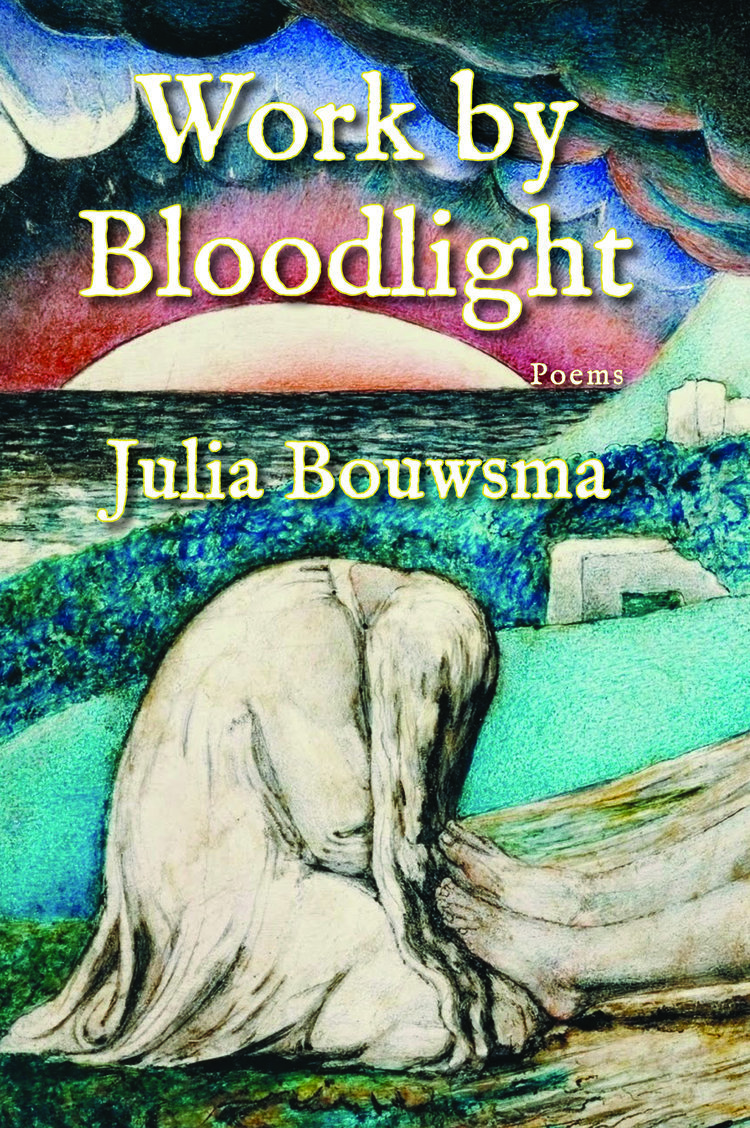

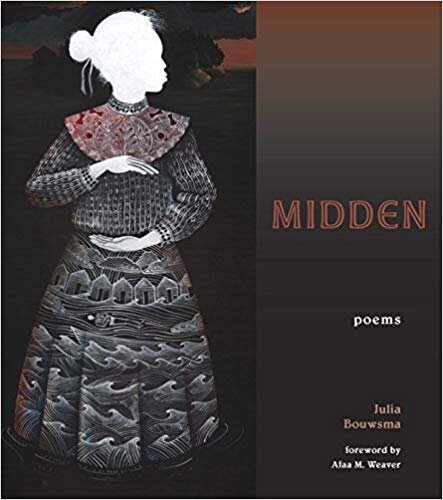

Julia Bouwsma lives off-the-grid in the mountains of western Maine, where she is a poet, farmer, freelance editor, critic, and small-town librarian. She is the author of two poetry collections: Midden (Fordham University Press, 2018) and Work by Bloodlight (Cider Press Review, 2017). She is the recipient of the 2018 Maine Literary Award; the 2016-17 Poets Out Loud Prize, selected by Afaa Michael Weaver; and the 2015 Cider Press Review Book Award, selected by Linda Pastan. Her poems and book reviews can be found in Grist, Poetry Northwest, RHINO, River Styx, and other journals. A former Managing Editor for Alice James Books, Bouwsma currently serves as Book Review Editor for Connotation Press: An Online Artifact and as Library Director for Webster Library in Kingfield, Maine.

Julia is the 2019 recipient of the Maine Literary Award for Poetry. Her latest book, Midden, is published by Fordham University Press.

Excerpt from Midden by Julia Bouwsma.

In Conversation:

with poet, Julia Bouwsma

You live off grid in western Maine. I'm wondering how you arrived at the decision to be off-grid? What does "off-grid" mean to you and what does that look like on a day to day basis?

The idea of finding a piece of land to connect to began for me in late high school / early college. Growing up in New Haven, CT, I’d read a few memoirs by back-to-the-landers (Mark Vonnegut’s Eden Express was the one that especially struck me), and then when I went to college I met someone from a family farm in rural Maine who became my best friend and then my partner. Finding a piece of land became our shared dream. After I graduated, we spent a year driving around the country, getting to know the American landscape to see where we most wanted to live. And ultimately we ended up in western Maine, about a half hour from the hill farm where his family lives.

The term “off-the-grid” is in some ways a technicality. It refers primarily to the fact that we are not on the electricity grid. But we do have solar power and a generator, and we have internet access, on which I’m unfortunately fairly dependent. With technological advances developing so rapidly these days, I just don’t think the term carries all of the hardship that it used to. And we are striving to make our home and lifestyle progressively more comfortable. That said, there have been times when we didn't have electricity or running water, when I carried buckets of water from the well daily. And there were quite a few years where we couldn’t drive all the way to our house year-round, and we walked or snowmobiled our groceries in from December to May. We heat our house with wood, so there is always the task of felling trees, of cutting, splitting, stacking, and hauling firewood, of cleaning out the ashes and laying a fire. We also have large vegetable gardens, raise pigs and layer chickens, boil our own maple syrup, make our own hard cider.

It’s an interesting irony to me that in some ways my desire to live “off-the-grid” stemmed from a sense of misanthropy and dislocation, a desire to feel removed and disconnected. But what really ended up happening is that it brought me a much greater sense of connection—to the natural world, to my own body, and to my rural community.

You mention misanthropy and dislocation leading to connection. How long did it take for you to develop this sense of connection to your homestead? Is it something that stays with you when you venture to a more urban environment?

I think my sense of connection to place was immediate and intense. In fact, I think it was so quick that it rather astonished me. I recall visiting Philadelphia (where I’d moved from to Maine) only about three months after relocating and feeling overstimulated by the city in a way I hadn’t expected. That has stayed with me in some ways. When I travel I’m often quite homesick, don’t sleep very well, etc. Of course I enjoy the restaurants, conveniences, and cultural institutions I can find in cities, but I like to suck that up in quick bursts and then return to my land where I feel most at home.

My sense of connection in terms of community was a much slower process. Culturally, rural western Maine is so different from where I grew up in New Haven, CT that it felt necessary for my to kind of hang back initially, to focus on listening and learning and on my writing. It wasn’t really until 2015 when I took a position as the librarian for my local library that I began to take on a really active community role. But when I did it was a real game changer for me. I think it helped me to start the work of understanding and building literary and writing community for myself in a much more active and conscious way, and eventually to start applying that to representing my work in the world once my books were published.

The land you live on and the work you make are intertwined. Did that happen naturally or was it something you actively sought? Was there a moment where you made a decision to focus on this particular subject matter?

The intertwining of my creative work and my relationship to my land developed very organically, and I don’t think I fully identified that it was happening until the process was pretty well underway. I was twenty-eight when we moved here, newly graduated from an MFA program and working on a first book that dealt with my very difficult relationship with my father. I was balancing the work of writing, and of developing my poetic voice, with daily physical labors that were very new to me. And slowly these other poems started to creep into this book that had started as a book about my father. Poems about farming, about the brutalities and beauties of raising animals, particular and tangible cadences built on walking the woods, on hauling, carrying, digging. My poems, which were initially fairly abstract and mythological, became very grounded, very physical, muscular even. My lines became longer and more sonic, my images more concrete. And as I tried to figure out how to blend poems about my childhood with these new poems in order to create a cohesive first book, I came to understand and value the ways in which two very different types of work fed and shaped one another. And I came to realize that my creative practice was going to be one of balancing abstraction and physicality, of allowing my head to wander and imagine while my hands and feet worked the land around me. Once I realized these things, I started to more actively build a practice around this symbiosis, but it wasn’t something I initially foresaw or set out to do.

I'm curious, what made you decide to write a series of poems about your relationship with your father? You began that work while in grad school. How did being in a writing program affect your work? Do you find that your work begins with something personal and then tackles a larger idea?

After my first semester in my graduate program, my advisor told me that I needed to ask myself what were the poems that needed me to write them? My poems were processing on a craft level, but emotionally I was holding back, avoiding taking a certain level of risk. When I began trying to really consider this question and what it would mean to write into the things that troubled me, the poems about my father began to emerge. They were poems about my father, but in retrospect I see they were also very much poems in which I was casting off an inherited mythology and creating one of my own. Which is really what I think about 99% of first poetry collections are, coming of age narratives really. So the father character in Work by Bloodlight is there because he ultimately has to be destroyed, reduced to archetype, so that the speaker can eventually cast of his influence and develop a new a new narrative for herself, one of intention, connection, and active accountability as built through an intense connection to place.

The idea of a conversation between the personal and something larger is at the route of almost all the poems I’m drawn to these days, and I think that’s representative of the direction contemporary poetry seems to be taking. Of course there are a million ways to create a conversation between the personal and something larger. I love seeing new techniques and conversations in poetry as a reader and I love experimenting with them as a writer. In Work by Bloodlight I started with something very personal and then moved into understating how it was engaging something larger. In Midden I started with a history that was much larger than myself and then had to work to locate my personal experience within that. In my future work, I expect to see this conversation continuing to take shape in all kinds of different ways.

““My poems, which were initially fairly abstract and mythological, became very grounded, very physical, muscular even.” ”

When I am working outside, something happens that purges out the non-essential and clears the mind. Is this similar to what happened for you in writing Work by Bloodlight? Or was it more through the process of writing itself? Can you elaborate?

What I mean here is that the cadences of outdoor labor—the physical rhythms of digging, of splitting wood, of walking—began to show up within the poems themselves. The lines got longer, more sonic. The poetics became more physical. I could hear it, see it, feel it: how the images and rhythms of my life as a homesteader began to appear in the work and to offer a grounding, tangible structure for my more abstract moments. And I began to learn how to weave these two tendencies together in poems so that each could serve to feed the other.

For your first book, Work by Bloodlight, you said, "I came to realize that my creative practice was going to be one of balancing abstraction and physicality". How do you find balance between the two? Is there a process you go through to vet out ideas?

Balance, for me, is really just sort of a philosophical, guiding concept. An intuitive part of my practice. It's a matter of approach, rather than something inherent in any one idea. It’s something I’m feeling for but resistant to pinning down. Lately I’ve been really interested poetic approaches that work to weave or braid a lot of disparate elements together—through collage, received forms, or orbital narrative structures that move around ideas, mapping their various threads rather than trying to relay them linearly. I’m interested in working to create poems that are more complex and expansive but that still retain a certain piercing clarity.

What are three of the most important things you have learned or value, living where and how you live?

Connection, accountability, and the importance of process.

Stay tuned for the next installment of this conversation.

Published Books:

Recent Events:

May 9, 2019, 7 PM

Reading, with Keetje Kuipers and Chen Chen

Word Barn—Exeter, NH

May 4, 2019, 2 PM

Reading

Curtis Library—Brunswick, ME

May 2, 2019, 7 PM

Reading, with Dzvinia Orlowsky

Collected Poets Series

Mocha Maya’s Coffee House—Shelburne Falls, MA

April 29, 2019, 7-9 PM

Reading, with Henk Rossouw

KGB Bar—NY, NY

April 27, 2019, 7 PM

Reading, with Henk Rossouw and Asiya Wadud

McNally Jackson Booksellers—NY, NY

April 4, 2019

Reading, with Richard Foerster

York Public Library—York, ME

March 27th-March 30th, 2019

Association of Writers and Writing Programs Conference, Portland, OR

Stay tuned for the next installment of this conversation.